In Harvey's wake, Texas can lead innovation in rebuilding for disaster preparedness

Officials at the Texas Department of Public Safety's Division of Emergency Management coordinate the state, local and federal response to Hurricane Harvey on Sept. 1, 2017. Photo by Bob Daemmrich

The devastation caused by Hurricane Harvey is a stark reminder that Texas is situated in a precarious region, the Gulf of Mexico, and is subject to a variety of natural and man-made threats.

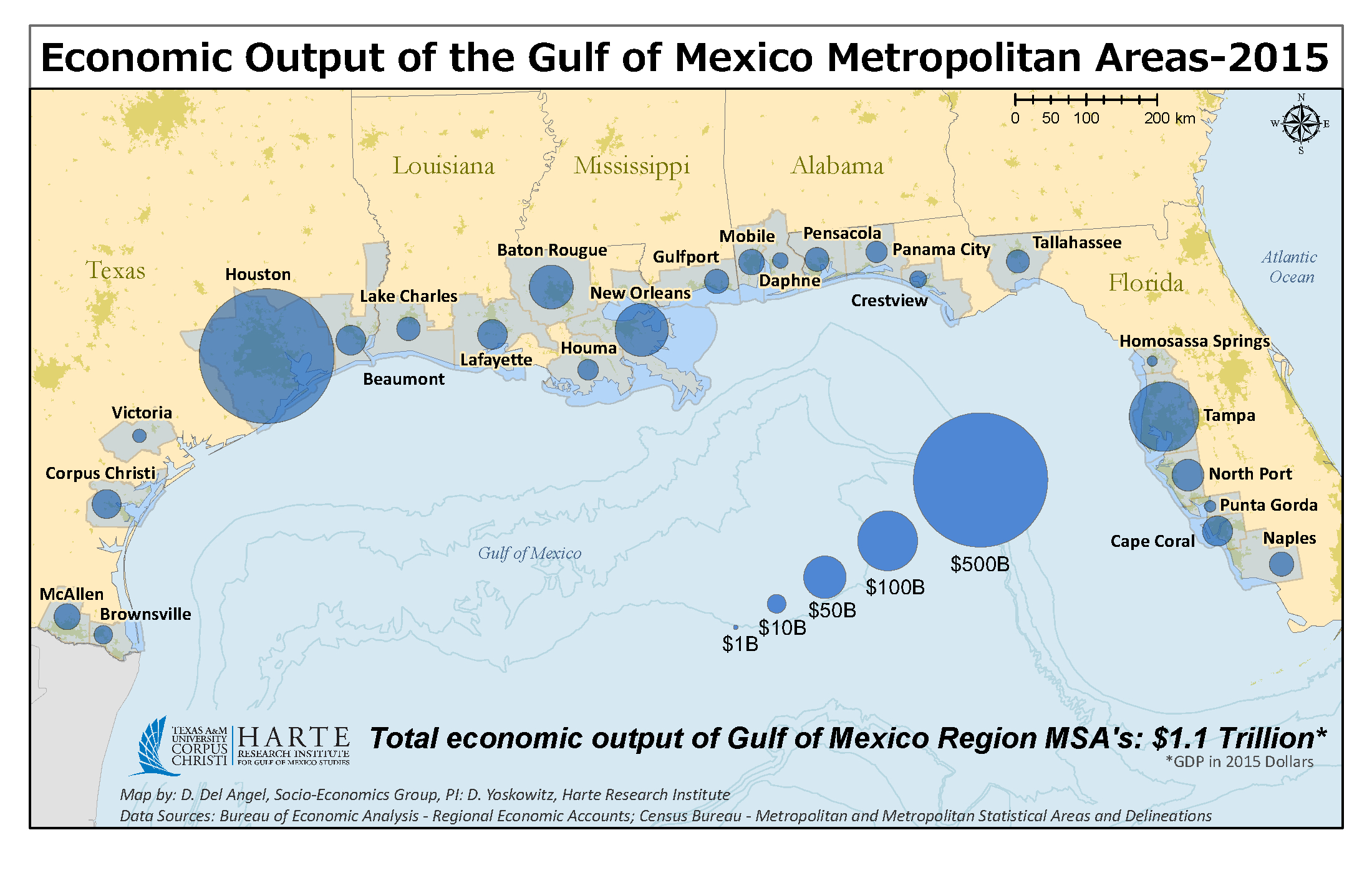

For the nation on the whole, the Gulf is a critical asset and a growing population center, with U.S. metropolitan areas generating $1.1 trillion in economic output in 2015. Coastal populations in Gulf states are expected to grow from 44.2 million to 61.4 million by 2025, with Texas and Florida leading the way. The region also is vital to our energy security, with more than 45 percent of the nation’s petroleum refining capacity and 51 percent of natural gas processing capacity. The Gulf hosts 13 of this country’s 20 largest ports, and is a major hub for our seafood industry. In 2009 commercial fishery landings totaled 1.4 billion pounds, generating more than $16 billion in sales and 100,000 jobs. Statistics on recreational fishing are equally impressive, with 2.5 million Gulf anglers spending $10.4 billion on trips and goods in 2015.

Texas and our national assets are increasingly at risk from climate and environmental change. While we cannot say that the extremeness of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma were caused by climate change, a draft of the Climate Science Special Report has found that the last few years have seen “record-breaking, climate-related weather extremes” and “the three warmest years on record for the globe.” The report also finds these trends are expected to continue.

In Harvey’s wake, Texas has an opportunity to lead the nation in demonstrating that society and infrastructure can adapt to changing conditions while creating harmony across varied interests.

As I write this, Congress is passing a $15.25 billion Harvey aid package to help Texans recover from the destructive storm. Most experts expect significantly more funding for longer-term recovery efforts to follow. In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, which caused $65 billion in damage along the East Coast, Congress authorized $9.7 billion in immediate relief, but ultimately provided more than $49 billion to help communities rebuild. As a member of the Hurricane Sandy Task Force required to create a Rebuilding Strategy for the funds, I learned two points that may be helpful for Texans to consider as we start to rebuild.

First, an investment strategy that is shared by state, local and federal officials can help leverage large federal programs and dollars toward fortifying communities against future disasters. Strategies should be forward looking, focusing on recouping losses but also addressing current and future risks across infrastructure, society and the environment. However, the majority of recovery funding likely will go to rebuilding cities and towns as they were — addressing yesterday’s problems. This is for a host of reasons, including time constraints for spending recovery dollars; difficulties in gaining federal support to mitigate impacts of future disasters; understanding multiple funding streams and regulations; and the longstanding tension between balancing long-term hazard mitigation investments with short-term economic development goals.

Which raises the second point: One way to overcome these challenges is to reserve a portion of recovery funds for innovation through a proven American tradition — competition. Following the release of the Sandy funding, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) collaborated with the Rockefeller Foundation to launch Rebuild By Design, a multi-stage competition that invited proposals for innovative, implementable schemes to enhance the region’s capacity to weather future disasters. By 2014, HUD announced $930 million in disaster recovery grants as seed funding to implement top designs. The projects continue today and each has leveraged additional dollars to continue their work.

“The Big U”, a winning Rebuild By Design proposal developed for the City of New York. Once complete, the Big U will protect 10 continuous miles of low-lying geography, shielding the city against floods and stormwater while also providing social and environmental benefits.

Perhaps one of the greatest achievements of Rebuild was that it required experts to work with communities in crafting designs that locals wanted. It convened stakeholders from government, business, academia, non-profit and community organizations to better understand how overlapping environmental and human-made vulnerabilities leave cities and towns at risk, and how we can use the rebuilding process to design a better future.

Texas now has a similar opportunity to help the state and nation leap forward in disaster recovery. We have a chance to show what we can do with our renowned disaster resilience experts, industry partners, engineers, architects, natural and social scientists, and our state and local community leaders and citizens. We can show that, as we saw during Harvey, Texans have the most stubborn, unrelenting care for their communities. We can lead the way in developing the new standard for recovery by embracing dialogue, innovation and design excellence. We have the talent, the determination and will likely have some funds. We need only the directive to act.